Climb a Tree

It has been said that it only takes one “Ah, NUTS!” moment to erase a thousand “Atta boys,” and it’s true that our more embarrassing moments tend to stick with us more than our triumphs. Just ask Bill Buckner. This tendency is observable from early in our lives when you think about high school. The cliques and the peer pressure and that embarrassing thing you did in freshman year that no one will let you forget. Or is that just me?

One would think that as we grow and mature that such preoccupations with a man’s flaws would attenuate as awareness of our own flaws accumulated, but no such luck. And what’s worse is that lately it seems more righteous to more people to censure publically—sometimes catastrophically—our heroes and public figures for their “ah, nuts” moments and forget their “atta boy” triumphs no matter how significant. There is no man, apparently, worthy of being considered great, the equation between success and failure is just too far skewed to the failures.

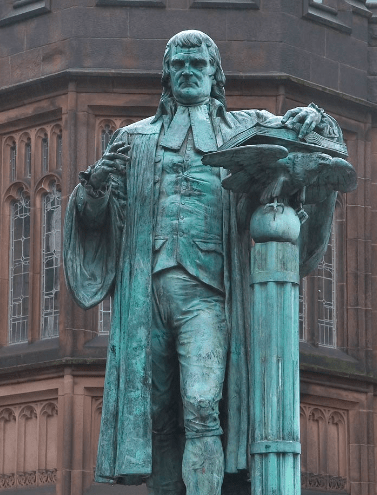

A good example of this is the recent petition at Princeton University to remove the statue of its 6th President and US Founding Father (the only clergyman and university president to sign the Declaration of Independence) John Witherspoon. His influence on the young republic was profound. Not only did he turn the College of New Jersey into what would become one of the finest universities in the world,

“He was a shaping influence on James Madison, especially on the necessity of checks and balances in government. His other students include Vice President Aaron Burr, 37 judges—including several members of the Pennsylvania Supreme Court and 3 U.S. Supreme Court justices—10 cabinet officers, 12 members of the Continental Congress, 28 U.S. Senators, and 49 U.S. Congressmen. Because of his work shaping so many who influenced the early years of the American Republic, Witherspoon was arguably the most influential of America’s founders.”[i]

Witherspoon both provided the place and fostered the freedom where and in which future students of his college would debate removing a statue erected in his honor.

The vice sufficient for his downfall is that typical of most defenestrated heroes of our history, a “complex relationship to slavery.”[ii] Though he spoke out against slavery and taught that slaves and employees should be treated with dignity and respect, Witherspoon owned slaves and opposed abolition through legislation, believing—as many at the time did—that slavery would die out on its own.

The funny thing about this particular sin is how many modern pseudo-historians are certain that they would be free of the same sin had they been alive at the time. Unlike most of the Founding Fathers, they would have been abolitionists. Professor Robert P. George finds this to be true in his classroom at Princeton, in which students all believe they would have been abolitionists, since slavery is so obviously wrong. His response is to ask them if they have ever risked their reputation, job, family, or life to take a stand that they knew would be unpopular. If not, he says, it is unlikely they would have opposed slavery.

What the exercise ought to teach all of us is that our descendants may have some harsh criticisms for how we conduct ourselves today, condemnations for things that are widely accepted now but later may become to them self-evidently evil or immoral.

But sticking your neck out is hard, especially if, like John Witherspoon, you’ve been dead for centuries. Take the case of Ivan Provorov. The only thing the Philadelphia Flyer did was refuse to wear a shirt during warmups that contradicted his Orthodox Christian beliefs in marriage, and he generated a media firestorm. As the Wall Street Journal put it in their headline, “Ivan Provorov Went to a Hockey Game, and a Culture War Broke Out.”

How many of us are willing to go as public with a culturally unpopular belief? If we aren’t willing then we’re in trouble, because the most unpopular cultural beliefs today seem to be whatever belief is held by Christians. And if you don’t think so, ask yourself how eager you are to share your faith with a coworker, or talk with a casual acquaintance about how important Church is to you and your family. Is your faith something you’re comfortable talking about at all amongst people with whom you don’t share it? Or would you rather talk about something else?

Not only is it difficult just to stick your neck out, knowing when exactly that you need to isn’t easy either, because when you’re standing in a crowd, you tend to go along with the crowd. Solomon Asche conducted one of the classic studies proving this tendency in 1951.

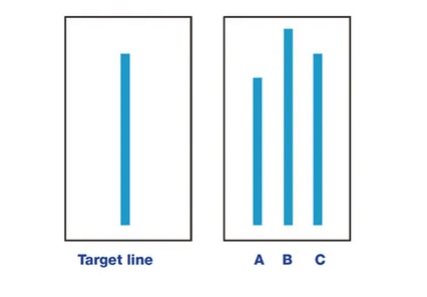

Asche ran a series of tests putting eight people at a time in a room, one a volunteer test subject and the rest—unbeknownst to the volunteer— all stooges chosen by Asche. The participants were to say aloud which line on the right was the same length as the target line on the left. The seven stooges went first and, as coached, all uniformly pronounced line “B” to be the same length, and 75% of the time the naïve volunteer would agree with the obviously incorrect choice (the correct answer is “c”). At the conclusion of the experiment, when asked why they had gone against the evidence of their own eyes, “most of them said that they did not really believe their conforming answers, but had gone along with the group for fear of being ridiculed or thought ‘peculiar.’”[iii] If such is the case during a meaningless test and with strangers, how much stronger is that impulse with matters of substance amongst people we love and respect.

Maybe Witherspoon should have spoken out more ardently against slavery and advocated for its abolition, but rather than judge him for his failure to do so we should take his plight as a warning not to think our virtue so superior, especially when we haven’t accomplished nearly so much good as to make the situation at all “complex.” If instead we exercise humility rather than hubris, we might get better at seeing through the popular culture to the underlying Eternal Truth, and that should make all of us uncomfortable for fear of what we may be getting wrong.

There’s a remedy to getting stuck in the crowd and going along with popular things that may in the end be the wrong things: go climb a tree.

In this Sunday’s Gospel reading, Jesus is drawing crowds in Jericho. Most of those drawn by curiosity seem satisfied to be a part of that crowd, but one man—a rich man, a swindler who made his fortune bilking his neighbors and countrymen— isn’t satisfied with being part of the crowd, Zacchaeus wants to see for himself what all the fuss is about. So he plans ahead, sees the direction in which the crowd is moving, runs ahead of them, and climbs a tree.

Zacchaeus is waiting up there just for a glimpse, just to see this guy everyone is talking about. Can he really be worth all of the attention he’s getting? But as the crowd approaches he gets more than he’d expected. Jesus looks him straight in the face and says “Zacchaeus, come down immediately. I must stay at your house today.” And so he does. St. Cyril of Alexandria says of this encounter that “as long as he is in the crowd, Zacchaeus does not see Christ; he climbs above the crowd and sees Him, namely, having transcended base ignorance, he deserved to perceive Him for Whom he longed.”

There is a warning in this story also: Be careful what you wish for, because rising above the crowd to look into the face of Eternal Truth will change you. It opens you to a wider perspective, to greater possibilities, and it frees you from slavery to your earthly passions. For Zacchaeus, whose passion was greed, that meant giving half of his goods to the poor and paying restitution to the victims of his swindling.

If you climb a tree, two things are likely to happen. First, it’s embarrassing. Grownups look silly trying to climb trees, so stiff and hesitant we’ve become. And if you think it’s embarrassing to make an honest mistake publically—your “Atta boy” erasing “ah, nuts” moment— just imagine what it is like when you know that what everyone thinks is a mistake is actually the truth. Ridicule is much harder to take when you can’t join in and laugh at yourself. But remember, St. Paul told us that God’s foolishness is wiser than human wisdom and the wisdom of this world is foolishness in God’s sight, so this is actually a good place to be.

Moreover, knowing the Truth is going to cost us. We cannot be the same person we were before. An honest confrontation with the Truth will reveal to us our own sin, as it did for Zacchaeus, and prompt action to correct ourselves and atone for the harm we have inflicted on others, because once we see Jesus we will also see the faces of our neighbors and know how self-centered we are and that our selfishness hurts everyone—ourselves included.

If you haven’t yet suffered much ridicule or payed much of a cost to be a follower of Christ, maybe you haven’t climbed the tree yet and are still muddling around with the crowd. Well, let all of us take advantage of Zacchaeus’ inspiration and get above the crowd. Let us seek the Truth wherever and whenever we can, no matter how embarrassing it is, no matter how much it costs. Though we may become isolated from the world, through Holy Communion, we will always be united together in Christ, who has already overcome the world. So don’t be afraid. Climb the tree.

[i] https://www.breakpoint.org/should-john-witherspoons-statue-remain-at-princeton/

[ii] https://slavery.princeton.edu/stories/john-witherspoon#2305

[iii]Asch Conformity Experiment – Simply Psychology