In an episode of the television show House a sick woman who is ill-treated by her boss plans to return to work for the same boss until she is confronted with her impending death. She then resolved she would do things differently in her remaining time and accept a leadership position at a non-profit foundation. Upon being healed, however, she reverts and decides to go back to her old job doing the same thing for the same people. When one of the doctors on his team is perplexed by the decision, Dr. House points out that “almost dying changes nothing. Dying changes everything.”

Dr. House is a curmudgeonly, rationalist atheist who doesn’t believe there is life after death, but his own professional and personal experiences force him to recognize that those who are left behind are changed by the death of a loved one, or even the death of an acquaintance. Whether we want it to or not, death does change everything.

It is only recently that our modern western culture has begun to forget this truth. These days we can hide from death and pretend that it doesn’t affect us. Warriors, on the other hand, cannot escape the reminder of death, and the constant reminder—particularly in combat—has profound spiritual impact. In his book What it is Like to Go to War, in which he describes combat as a “sacred space,” former Marine combat commander Karl Marlantes describes this phenomenon:

“Many will argue that there is nothing remotely spiritual in combat. Consider this. Mystical or religious experiences have four common components: constant awareness of one’s own inevitable death, total focus on the present moment, the valuing of other people’s lives above one’s own, and being part of a larger religious community…All four of these exist in combat.”

They are profound differences in perspective, but both the warrior and the religious keep the awareness of their death preeminent in their minds. For Marlantes, his confrontation with death put him into “a different relationship with ordinary life and eternity.”

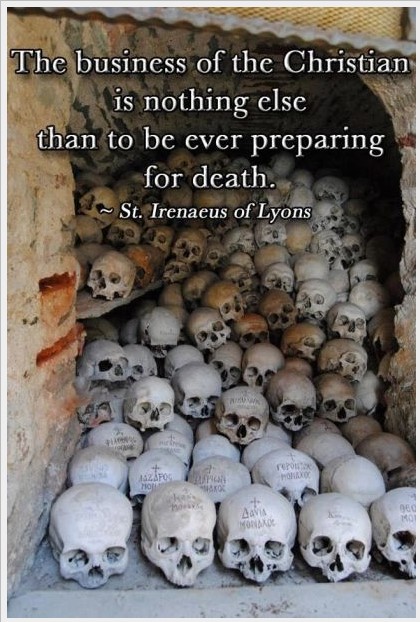

So warriors can answer “yes” to the question posed by St. Gregory the Theologian, “Do we make life a meditation of death?” Also in the fourth century, Abba Isaiah of Shiheet counseled us to “Keep death before your eyes daily, and be concerned about how you leave this body, pass the powers of darkness that will meet you in the air.” And then in the seventh century Abba Isaac the Syrian, exhorted, “Prepare your heart for your departure. If you are wise, you will expect it every hour.” These spiritual warriors had in mind the lesson from Sirach 7:36 “In all you do, remember the end of your life, and then you will never sin.”

This is part of the meaning of the Gospel in this Sunday’s celebration of the Holy Cross. The first step to following Jesus is to pick up our Cross, to remember our death, because it is in this that we are able to focus on what’s important, on eternal things. “For whoever would save his life will lose it; and whoever loses his life for my sake and the gospel’s will save it. For what does it profit a man, to gain the whole world and forfeit his life? For what can a man give in return for his life?”

Russian Saint Ignaty Brianchaninov describes a person who practices the remembrance of death in this way:

“He is constantly occupied with wondering what will justify him at Christ’s terrible judgment and what his sentence will be. This sentence decides a person’s fate for the whole of eternity. No earthly beauty, no earthly pleasure draws his attention or his love. He condemns no one, for he remembers that at the judgment of God such judgment will be passed on him as he passed here on his neighbors. He forgives everyone and everything that he may himself obtain forgiveness and inherit salvation. He is indulgent with all, he is merciful in everything, that indulgence and mercy may be shown to him. He welcomes and embraces with joy every trouble or trial that comes to him as a toll for his sins in time which frees him from paying toll in eternity. If the thought comes to him to be proud of his virtue, at once the remembrance of death rushes against this thought, puts it to shame, exposes the nonsense and drives it away.”

St. Ignaty called the remembrance of death “a bitter medicine against sinfulness,” because when we remember our impending judgement by, like Marlantes says, having a “constant awareness of one’s own inevitable death,” we will be better able to “focus on the present moment” and make right choices. But more than that it helps us develop the right relationship with this world, prioritizing eternal things above earthly things that don’t last forever—and certainly won’t concern us beyond our death. Ultimately, the remembrance of death helps us cultivate loving relationships with one another, because it exposes as petty all of the offenses and insults that we suffer, allowing us to value “other people’s lives above one’s own,” which is necessary if we are to be “part of a larger religious community” free of division and hatred.

Remembrance of death is picking up your cross and following Christ, it is dying to the world, and dying changes everything.