One significant difficulty faced by young Sailors is the product of one of the benefits of modern technology. Because of satellites and computers, our deployed service men and women can stay in touch with their family and friends back home. Even in the middle of the Atlantic they can access email and Facebook and communicate in real time, with only minor delays. While this is a boon to most, to some it can bring bad news, and often miscommunication. Chaplains spend a surprising amount of time working through one side of a relationship in distress because of something written in online messages or an email. More times than I can count I’ve been shown a screenshot of an offensive message and been at a complete loss as to why the offended party was so upset. Of course, I lacked the context in which it was sent, but even once it’s added it becomes clear that he or she—like all of us—is reading through a lens that can’t easily be changed and should seek clarification before responding. The easier it is for us to send messages, the more critical it becomes to seek understanding and be measured in our responses. I sought to make that point with this evening prayer.

Can you hear me now?

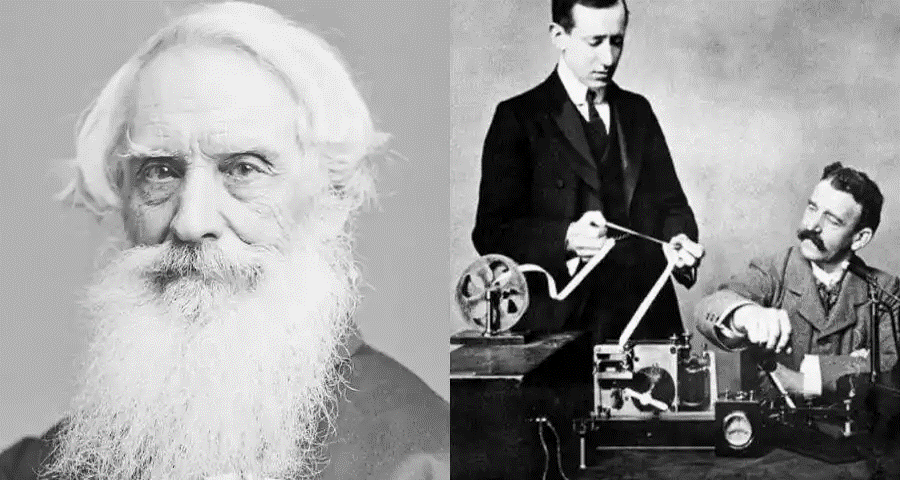

In a strange coincidence, last night we ran a signal light exercise, using the bridge signal light to flash a message to the Ike in Morse code, and today happens to be the anniversary of the 1st demonstration of the electric telegraph invented by the man for whom that code was named.

On May 24, 1844 Samuel Morse sat down in the chambers of the U.S. Supreme Court in Washington, D.C and used his brand new invention to tap out a message to his associate, Alfred Vail, who was 40 miles away in Baltimore. People like to talk about how much television or the internet has changed the world, but the invention of the telegraph was arguably even bigger.

For thousands of years, from before the dawn of history, no one could send any message farther than the eye could see unless it was physically carried. From before Alexander the Great all the way past Benjamin Franklin a galloping horse was the fastest way known to man for sending a message between far-flung locations. 179 years ago the telegraph changed everything and communication would never be the same.

The advancements in communication that have followed in the fewer than 200 years since have allowed us to communicate with men on the moon and speak to our families in just moments, even though we’re on the opposite sides of the planet. It has been said that the increasing speed of communication has progressed rapidly from telegraph to telephone to tell-a-sailor. And that last one is even faster if you’re communicating a rumor.

In 1858, 14 years after its invention, the New York Times feared that the telegraph was “too fast for the truth,” meaning that a message could be sent and received before it had been verified. As someone once said, “A lie can travel halfway around the world before the truth can get its boots on,” and if you watch the news these days you know that they aren’t too far off the mark.

Like every life-changing invention the telegraph came with lots of unforeseen challenges as well as the obvious benefits. Just because we make it easier to send a message does not mean that we are any better at communicating.

For example, any attempt to communicate in written form is limiting our expression only to the words we choose—and perhaps some strategic capitalization. There are no visual cues as to the mood of the sender or of the emphases he or she is trying to make. This is especially true in the case of text messages or online messenger communications. We communicate quickly, but not necessarily better.

In all cases and in every medium we can improve our communication if we do two things. First, when sending a message try to be as clear as you can. Be precise in your speech, choosing your words carefully based on what—exactly—you are trying to express. Then verify that you’ve been understood before moving on. Morse would never have known his invention had worked if his assistant hadn’t replied.

Second—and most important—when receiving a message make certain that you understand it correctly before responding. All of us have particular filters through which we hear or read things, so double-check that what you thought you heard was actually what was said—and meant. Trust me when I say that nearly everyone you talk to will not mind if you verify what he or she is trying to say. Doing so only shows your interest in understanding them better, and who wouldn’t appreciate that? Making a habit of doing this very thing has saved many relationships.

The first telegraph message that Samuel Morse sent was a quote from Numbers 23:23, “What God hath wrought.” In its power to transform society the telegraph could only be overshadowed by an act of God. If we could improve how well we communicate to one another and not just how quickly we do, that would be an even bigger deal.

LET US PRAY

Lord, you tell us that he who closes his ears that he might not listen to the weak, will call upon someone himself and find that no one will be listening. You also tell us that he who guards his mouth and tongue keeps his soul from tribulation. Help us, O Lord, to keep our ears open and listening with attention to understand, and guard our tongues to say only what is necessary and true. Teach all of us to lay these foundation stones of communication so that we might build relationships that endure. For You are the God of unity and communion, and You are holy always, now and forever and to the ages of ages.

AMEN