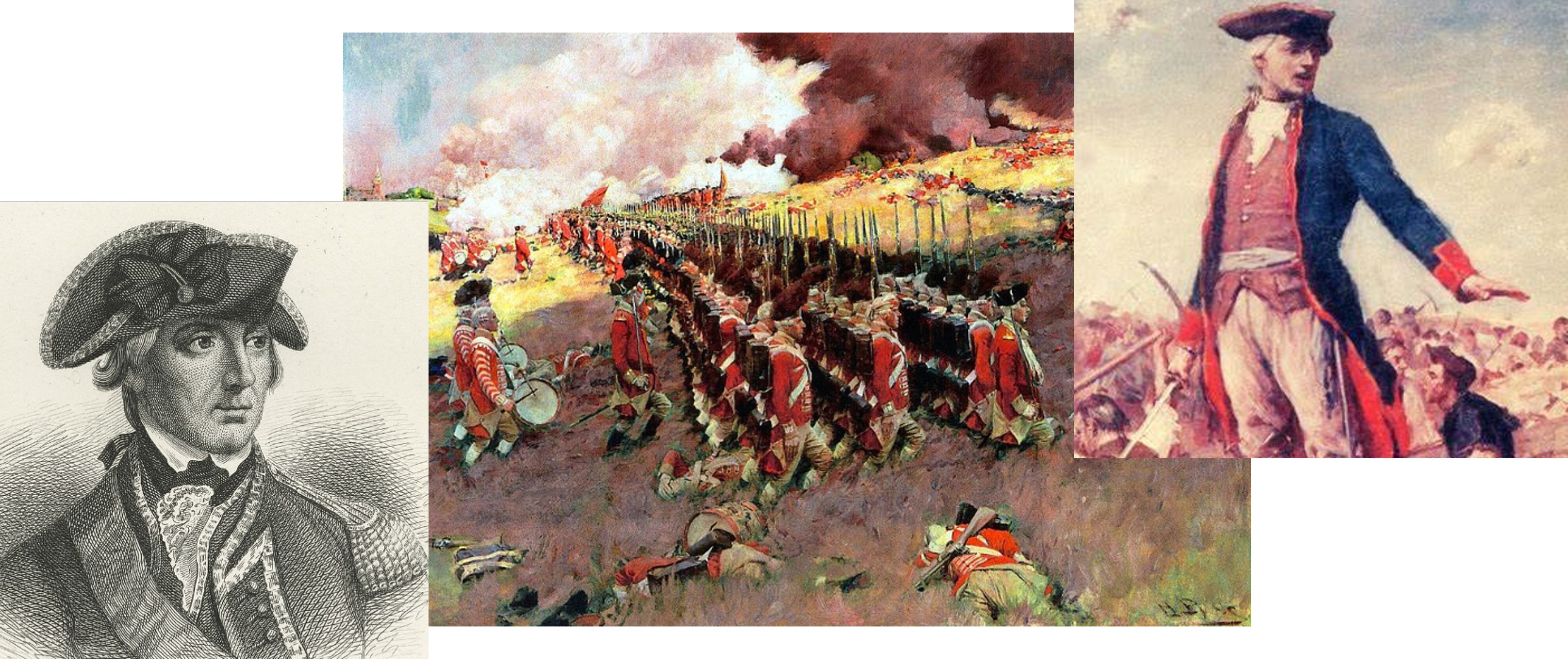

On the 17th of June 1775, some 2200 British soldiers under the command of Major General William Howe crossed the Charles River from Boston and landed on the shore of the Charlestown peninsula. The Royal Army had been trapped in Boston, under siege by the Colonial Militia. Recently reinforced by sea, the Redcoats planned to lift the siege by taking the heights across the river that commanded the town and were the extreme left of the Colonial line.

Not Every Defeat is a Lost Cause.

The British did not expect a very stiff or prolonged resistance. The only thing standing between them and the hilltop was a motley collection of colonial militia, not exactly the kind of vaunted opponent that the Royal Army had become used to meeting in combat around the world. The king’s best troops would be taking on farmers, fishermen, and merchants who were defending a position they had only just established that morning. General Howe was certain of success.

Filing into lines abreast, the Redcoats began their assault at 3pm with a force that far outnumbered the awaiting defenders. The Colonials had been unable to bring up any supplies before the assault and so had limited ammunition. With this in mind, as the wave of red climbed toward his position, Colonial Commander Colonel William Prescott told his men to hold their fire until the British were close enough to see the whites of their eyes. Tense and nervous the men waited. And waited. When they finally did open fire, the effect was devastating, knocking the British assault back down the hill.

Back where they started, they regrouped, reformed their lines, and began a second assault that ended with the same result. As the Redcoats ascended in their third assault the colonial fire sputtered and died as each man ran out of powder. The defenders received the British attack in hand-to-hand combat until forced from their positions by their inability to return British fire.

Howe won his expected victory, but at an unexpected cost. 1054 Redcoats had fallen in their attack on the colonial position on Breed’s Hill. Compared to the 450 American Patriots killed or wounded the Battle of Bunker Hill—named for the bigger adjacent hill that was the objective of both armies—was a pyrrhic victory for the Royal Army. General Howe lost his entire staff in the engagement, and later said that “the success is too dearly bought.” The losses they sustained would eventually force the British to abandon Boston.

More importantly it proved that Colonial Militia could effectively fight the British Royal Army. This in turn had the dual effect of emboldening the fledgling Continental Army and prompting a new approach by British generals to their conduct of the war. Both effects favored the Americans and led to the eventual defeat of England.

We don’t typically like to remember our defeats, but not only do we remember Bunker Hill, we celebrate it, because in spite of the odds of near certain defeat, men in support of a just cause did the right thing and acted courageously and heroically.

It’s a good thing to remember the next time we suffer a personal defeat. We have nothing to be ashamed of if we did the right thing—the courageous thing—even in a losing effort, especially if we learn from it.

LET US PRAY

Almighty God, as we remember today the heroes who lost a battle, may we be encouraged to sustain our struggles even when everything seems set against us, because, thought they lost a battle, they won the war. Help us to focus less narrowly on particular victories so that we can pay attention to how we conduct ourselves, and thereby win the long-term victory. Help us always to do the right and courageous thing, for You are the God of justice, mercy, and humility, and You are holy always, now and forever and to the ages of ages.

AMEN