At age 19, James Goodson was positive that America would eventually jump into the battle against Nazism, yet he decided not to wait. He packed his bag and set sail for England. While transiting the Atlantic, Goodson’s ship was torpedoed and sunk, and he arrived in England with just the clothes he was wearing. Here is what happened next:

I found a RAF recruiting station and immediately asked if any American could join. No one seemed to know at first if I could but later was told I could but would probably lose my American citizenship when I swore allegiance to the King of England. I told the recruiters that if the king needed my allegiance, he had it. The question of pay arose and I think the fellow said it was seven shillings and six pence a day (less than $2.00). I was heartbroken. I said, “I’ve lost everything I have. I don’t think I can afford it.” The fellow said, “No, no, no. We pay you seven and six.” I remember thinking, “These lovable fools. They could have had me for nothing.”

Goodson survived the war and returned home with the US Army Air Corps, but only after shooting down fifteen enemy planes and earning the British Distinguished Flying Cross, the American Distinguished Flying Cross 9 times, and the U.S. Air Medal 21 times, among other decorations including the Purple Heart. He was a hero who responded—even before his nation did—to the call to arms.

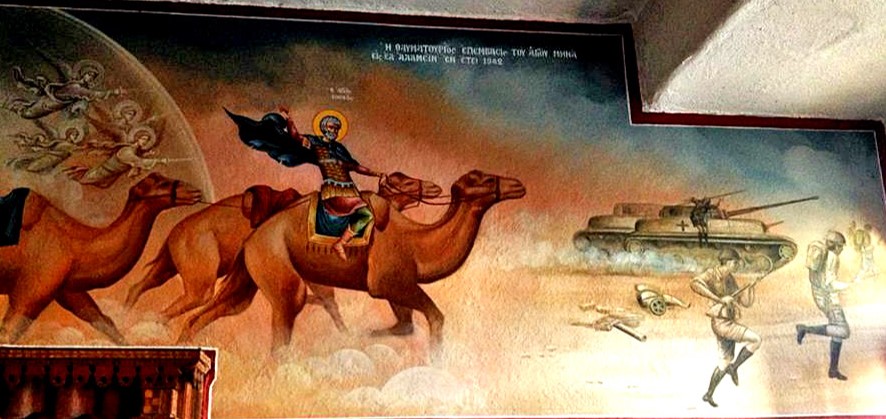

The Orthodox Church enjoys an embarrassment of riches when it comes to warrior saints. Throughout the centuries warriors who first answered the call to earthly warfare, thereafter turned to spiritual battle. Our monasteries preserve their icons because the life of spiritual warfare so closely mirrors that of the earthly soldier’s life, filled as it is with commitment, discipline, and training. In many ways, the warrior’s life is a cross taken up on behalf of his fellow countryman, and this is why they offer a model for the Christian life.

Author Anthony Esolen was one of the few to see coming the present chaos in sexual politics while it was yet confined to the fringes of popular consciousness. He was fired from his professorship at a Catholic University for writing things that were simply Catholic. Aware of the coming storm, he wrote an article wherein he describes the soldier, what makes him unique, and why we need him.

One of the marks of a warrior-saint is his willingness, like James Goodson, to go to war, to gather his courage and face the growing threat of his enemy. Esolen writes that “the Soldier complains about his superiors not because they give him bad orders, but because they give him no orders at all. He wants to do battle, and is willing to be led. He knows that war is hell, but that he and the Church have not sought the war.”

St. Constantine the Great saw his share of battle. He faced a superior enemy at the Battle at the Milvian Bridge, and though he commanded a force half the size of his opponent, he was willing to face his enemy. The historian Eusebius tells us how God granted St. Constantine a vision on the eve of his battle in which the warrior is told that he will conquer his enemy under the sign of Christ. So, when the enemy saw Constantine’s approaching army, they saw flying over them a flag with a symbol they’d never seen before. It was a Cross. Constantine’s army prevailed, and he would go on to unify both the empire and the Church in ways that have lasted to this very day.

I believe St. Constantine’s subsequent devotion to peace and unity came partly as a result of his conversion to Christianity, but also because of another attribute shared by warrior-saints: No one loves peace more than a warrior. The warrior has seen the cost of conflict, a cost paid in both blood and treasure, so he knows the inestimable value of peace. Young James Goodson would have paid his own money for the privilege of fighting the tyranny of the Nazis, but writing a check is easy when compared to laying down your own life. Yet there is no price the warrior-saint is unwilling to pay.

He is willing to pay that price regardless of his situation, when he knows his cause is righteous. It is easy to find excuses to quit the battle, or even to avoid it altogether, but Esolen reminds us that:

The Soldier does not say, “I will fight, but my generals must be perfectly wise.” Generals are never perfectly wise or perfectly anything else. The Soldier does not say, “I will fight, but only if I do not have to share the field with these others,” which others may be traditionalists, the ecumenically minded, Protestants friendly to the …Church, or [Christians] who disagree with him on some political point. The Soldier is grateful for his brothers in arms, and if their uniforms are a little different from his, he figures that the Lord of Hosts will sort the matter out in the end.

What this means for us is that we need to take courage from the example of St. Constantine and be willing to act, to take courage and face our enemies on the spiritual battlefield. And like Mr. Goodwin we must be willing to do it simply because it is the right thing to do, no matter who is in charge or with whom we are allied in pursuit of the same cause. Because when we speak the truth—even when it’s uncomfortable or costly, or when we stand up for someone—even if they don’t know about it or appreciate it, or when we help someone—even if they don’t ask politely or say thank you, it is in those moments of courage that we take the battle to the enemy. The harder it is to do this, the greater will be the victory, because as the Lord told St. Paul “My grace is sufficient for you, for my power is made perfect in weakness.” It is the very meaning of the Holy Cross, the sign under which we too will conquer. Like a warrior saint we must not shrink from the battle.

When we endure the struggles and the difficulties of battle, then we can truly appreciate peace. And the peace we receive is no ordinary peace, for Jesus said, “Peace I leave with you; my peace I give you. I do not give to you as the world gives. Do not let your hearts be troubled and do not be afraid.” When we face our spiritual battles under the sign of the Holy Cross, Jesus gives us peace—even in the midst of the battle. And it is a peace that is lasting and sweet and surpasses all understanding. What would you be willing to give for this peace? What battle would you not fight to gain it? Is it worth seven shillings six pence? Is it worth your life? St Constantine and all the warrior saints think it is.

It isn’t going to be easy, but taking up one’s cross never is. I close with Esolen’s words:

The Soldier does not make light of the desperate situation. His name is not Pollyanna. But he remembers the words of Jesus: “In the world you will have tribulation; but be of good cheer, for I have overcome the world.” The Soldier will not refuse a hearty meal, but he will not grumble if he has to fast. The Soldier is filled with thymos: his eyes narrow and look to the horizon; his nostrils flare and his heart beats with excitement; he sings Rise Up, O Men of God; he craves honor, most of all the honor of the Church; he does not care who calls him a fool. He is immensely attractive and wins the respect even of his enemies. He brings both men and women into the Church without that being his principal aim, because it is sweeter to spend one day in the field with the Soldier than a thousand in the halls of the wealthy, the powerful, the timid, the faithless, and the mad.

May God grant us the grace to be Soldiers—all of us, now. The war is here.