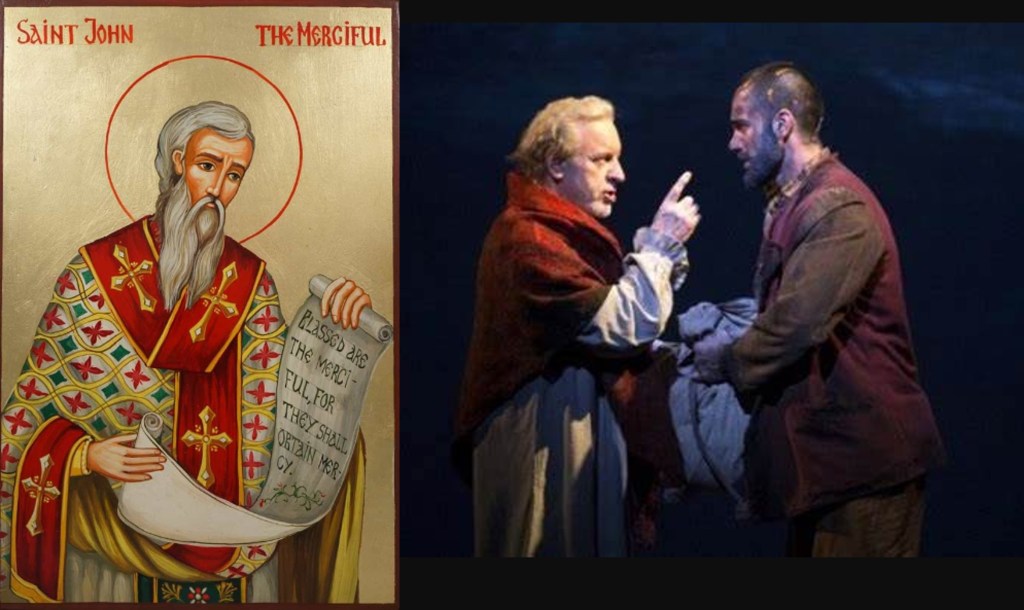

Today we commemorate St John the Merciful, who was born in the year 555 AD on the island of Cyprus to pious Christian parents. His father was the governor of the island and saw to it that his son received the best possible education. John married and had children, but his family perished while he was still rather young. Without a family of his own to care for, he made mankind the object of his care and concern. His piety and selfless acts of love became so well-known that they prompted Emperor Heraclius largely through the counsel of Nicetas, the adopted brother of the saint—and with the approval of the whole body of Alexandrians—to press for his elevation to the high-priestly throne as Patriarch. He was made Patriarch of Alexandria, from a lay state, in the year 608 AD.

According to The Life of St. John the Almsgiver, St John “is one of the very few Byzantine-era saints to gain a following in the West. He was one of the saints in the Golden Legend, but it was his role as original patron of the order of St. John of the Hospital, the Hospitallers, – one of the great Western crusading military orders – that made his name famous. This order still survives as the Knights of Malta, and, in the British Commonwealth, the “St. John’s Ambulance Corps” is named after him.”

There are many stories about the generosity of St John the Almsgiver, but one of my favorites is the way he treated a man who attempted to deceive him and impose upon his generosity.

Whilst this same crowd of people was still in the city, one of the strangers, noticing John’s remarkable sympathy, determined to try the blessed man; so he put on old clothes and approached him as he was on his way to visit the sick in the hospitals (for he did this two or three times a week) and said to him: ‘Have mercy upon me for I am a prisoner of war.’

John said to his purse-bearer: ‘Give him six nomismata.’ After the man had received these he went off, changed his clothes, met John again in another street, and falling at his feet said: ‘Have pity upon me for I am in want.’ The Patriarch again said to his purse-bearer: ‘Give him six nomismata.’ As he went away the purse-bearer whispered in the Patriarch’s ear: ‘By your prayers, master, this same man has had alms from you twice over!’ But the Patriarch pretended not to understand. Soon the man came again for the third time to ask for money and the attendant, carrying the gold, nudged the Patriarch to let him know that it was the same man; whereupon the truly merciful and beloved of God said: ‘Give him twelve nomismata, for perchance it is my Christ and He is making trial of me.’

https://sourcebooks.fordham.edu/basis/john-almsgiver.asp

The Almsgiver knew that the proper use of his alms was not his responsibility, it was only the giving of those alms that was his responsibility. And the same applies to us.

Which is why it is so very fascinating that we have the combination of readings that we find this Sunday. The Epistle reading is one that follows the saint and offers the inspiration for why he was so generous. He simply believed St. Paul when he wrote that “he who sows sparingly will also reap sparingly, and he who sows bountifully will also reap bountifully. Each one must do as he has made up his mind, not reluctantly or under compulsion, for God loves a cheerful giver.” This can apply to money and material things, but it applies even more if we sow love and generosity.

Too often we are afraid to give anything, fearing that we will have less for ourselves. But Paul goes on to assure us that “God is able to provide you with every blessing in abundance, so that you may always have enough of everything and may provide in abundance for every good work.” That Saint John knew this to be true is evident in the way he lived his life.

On top of St John’s example of generosity and St Paul’s epistle imploring us to give generously, we add today the Gospel for the 8th week of Luke, which contains Jesus’ parable of the Good Samaritan. It’s a story that we all know well, but in the centuries since its telling may have lost some of its impact. After centuries of living in a Western Culture imbued with Judeo-Christian values, we find it easy to judge the priest and the Levite for failing to help a man in need. We likewise find it easy to cheer the Samaritan’s charity.” Of course he should help,” we think, “we all should help anyone in need.” But this sentiment is a purely Christian one, almost completely foreign to the world of first century Jerusalem.

This is why the young lawyer asked the question that prompted Jesus’ story: “And who is my neighbor?”

This is no idle question in the first century, dominated as it was by honor cultures throughout the known world. To such a culture the only people one considers even human are the ones within your “honor group:” your family, clan, or tribe. Anyone beyond that circle is literally beneath contempt, so far outside one’s consideration that he or she isn’t even worth hating. It is this kind of culture that produces revenge killing, and other more heinous acts, to punish those who violate the integrity of the honor group. When people look at the Old Testament and see a vengeful God in the Levitical law, it is only because they don’t understand the culture into which God was speaking, and that God was actually limiting the scope of retribution committed in the name of honor and justice.

So, to this questioning lawyer, his neighbor would almost certainly be limited to his Jewish tribe. Jesus knew this, and so he made the model neighbor a Samaritan, someone so far outside the lawyer’s honor group that he would have been beneath contempt. Were the Samaritan the one who fell amongst theives, this lawyer would likely have left him along the road to bleed to death with no doubt that the victim deserved his fate.

For us to feel an impact similar to what this lawyer might have felt, let me turn to a more recent parable. This one is a story found in my favorite musical, Les Miserables. The story I’m thinking of involves a character who receives little stage time in the musical but took Victor Hugo 14 chapters to describe. They are the first 14 chapters, and they describe the bishop. Bishop Charles-François-Bienvenu Myriel, referred to in the novel as Bishop Myriel or Monseigneur Bienvenu.

On stage the bishop is the only one who welcomes the recently released ex-convict Jean Valjean into his home for warmth, a hot meal, and a bed for the night. A luxury for which Valjean is not expected to pay. The depth added by the novel’s description is that Valjean thinks he’s dining with a humble parish priest, because this bishop has sold everything of value in the bishop’s mansion, which is now the hospital next door, and is living on 10% of his rightful wage in a humble lodging that used to be the hospital. Hugo’s Bishop Myriel practiced the kind of charity reflected in the life of St John the Merciful. In fact, the narrator of the novel describes him this way:

There are men who dig for gold; he dug for compassion. Poverty was his goldmine; and the universality of suffering a reason for the universality of charity. ‘Love one another.’ To him everything was contained in those words, his whole doctrine, and he asked no more.

The only thing of earthly value that the bishop kept was the silver on which their dinner was served, the silver that Valjean steals that very night.

Valjean is caught the next morning and returned to the bishop to explain himself. Though the musical tells this story, it tells it backwards. Maybe the authors of the stage play thought it too implausible to believe, but when the bishop sees the police bring Valjean in, he doesn’t even give them time to explain what’s going on. He leaps from the table where he is eating breakfast with his hands, runs to the mantlepiece to grab the two large silver candlesticks that are the only remaining silver in the house, and gives them to the thief, admonishing him that he forgot to take them. He then tells the police the same story they’d heard from the thieving Valjean—seeking to justify himself—that the silver had been a gift of the bishop. As the police leave the bishop says to Valjean, “Do not forget, do not ever forget, that you have promised me to use the money to make yourself an honest man. Jean Valjean, my brother, you no longer belong to what is evil but to what is good. I have bought your soul. To save it from black thoughts and the spirit of perdition, and I give it back to God.”

Valjean never made that promise. But the Bishop’s love and generosity produced more love and generosity in the life of a transformed Valjean. The bishop’s neighbor, his “Christ…making a trial of him,” was a man who stole from him.

If we are to love our neighbor as ourselves, we must love whomever that may be-especially those who make a trial of us. If we are to reap love and generosity, we must abundantly sow love and generosity. If, on the other hand, we continue to cross to the other side of the street rather than help a fellow human being in need, we are sowing something else, and we will eventually reap that too, just as abundantly as we sow it. We are pretty good at blaming other people for the problems in our lives. It is far more productive to look and see what kinds of seeds we are sowing if we truly want to understand the harvest we are reaping.

Ultimately, as Jesus told the lawyer, simply knowing the commandments isn’t enough. We must do them: we must love, we must have mercy. Because this is what God does towards us every day. Though He created us, He considers us His neighbor—even when we make ourselves his enemy. Going so far as to make Himself like us, subjecting Himself to the mess we made of the world, in order to reconcile us—His enemy—to Himself. He is immeasurably loving and generous to us who would steal from Him all that we could. If we call ourselves Christians, then we must do the same.

May the Holy Spirit indwell all of us and give us the strength to “go and do likewise.”