This week we celebrated the feast of the Presentation of the Theotokos in the temple. This is one of the three great feasts—the other two being the Nativity of the Theotokos and the Dormition of the Theotokos—whose stories are not told in any of the four canonical Gospels, Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John. The story of this feast is told in the Protevangelium of James. I know: what is that?

The Protevangelium of James, or Gospel of James, is a second century text detailing the early life of the Virgin Mary. It isn’t long and you can read it here. The James referred to is usually believed to be St. James the Less, the Lord’s brother. Origen and St. Justin Martyr are two of the earliest witnesses to either the book itself or the stories it contains. Evidently, they were being told early enough to be heard by eyewitnesses to some of the events related by the author.

Even so, this so-called Gospel of James, though the source for much of what we know of Mary’s life and childhood, also contains some material that even at the time was found to be dubious. For this reason, and for some doubt about its authorship, it was never seriously considered as part of the canon of holy scriptures. Don’t let that fact diminish its value in your estimation, however. There has always been a hierarchy to the Holy Scriptures, and not even within the canon are all the books of the Bible considered equal.

The Four Holy Gospels, for example, the books containing the accounts of Jesus’ life and teachings are the only ones kept on the Holy Table and only the priest reads them during divine services. Apostolic epistles are the only other scriptures read during a Divine Liturgy, and the books of the Old Testament are only ever read during the hourly offices, Orthros, and Vespers. Some books are never read during divine services but are still used in the Holy Tradition and teachings of the Church. The Revelation of St. John, for example, though part of the canon of Holy Scripture and in the Bible is never read during the Divine Services.

Then there are other books.

“Apocrypha” (from the Greek for “out of hiding”) has different meanings for various groups when it comes to scripture. Protestants who grew up with the Authorized Version, King James translation (KJV), are familiar with 66 books in their Bible, 39 in the Old Testament and 27 in the new, and most could probably list them in order. But, though initially included, the KJV soon began to exclude some books that the early Christians considered part of Holy Scripture and are included in the Latin Vulgate, the Bible of the early Catholic Church, and the Septuagint Bible (LXX), which is the Old Testament Bible that the Church Fathers used—especially in the east.

The difference is some 14 books that Protestants refer to as “Apocryphal,” but which the Church—at least until the Protestant Reformation—considered canonical and referred to as the Deuterocanon, literally the “Second Canon.” They were part of the Holy Scriptures, but held to lower esteem than the primary canon, within which was its own hierarchy that I referenced above. At the bottom of the hierarchy of scriptures are what the historic Church referred to as apocryphal, books that were read for instruction only. Among these latter is the Gospel of James.

It is never read in Church services, even during the Divine Liturgies celebrating events contained within it—like the present feast. The stories it contains, however, were accepted very early, from at least the middle of the second century AD, and were key in developing the popular piety towards Mary the Mother of God that resulted in the feasts now part of the Church calendar. They survived even condemnation by Popes. But why bother with them at all?

When the ancient Christian Church, a Semitic religion, first encountered Greek philosophy in a meaningful way, the confrontation generated a lot of controversy. Bishops like Tertullian, who wondered “what has Athens to do with Jerusalem,” opposed the influence of Aristotelian and Platonic ideas on Christian theology. Even in the fourth century the Church was still struggling to understand who and what Jesus is, and such men feared the Hellenic influence would pervert or diminish God.

St. Basil, however, disagreed. His moderated but opposing view held that creation will necessarily reflect its Creator, and that earnest and thoughtful men seeking truth will find Truth, and encounter God, even if only in a diminished and obscured way. He recommended we consider such sources of truth as the bee considers flowers:

For the bees do not visit all the flowers without discrimination, nor indeed do they seek to carry away entire those upon which they light, but rather, having taken so much as is adapted to their needs, they let the rest go. So, we, if wise, shall take from heathen books whatever befits us and is allied to the truth, and shall pass over the rest. And just as in culling roses we avoid the thorns, from such writings as these we will gather everything useful, and guard against the noxious. So, from the very beginning, we must examine each of their teachings, to harmonize it with our ultimate purpose, according to the Doric proverb, ‘testing each stone by the measuring-line.’

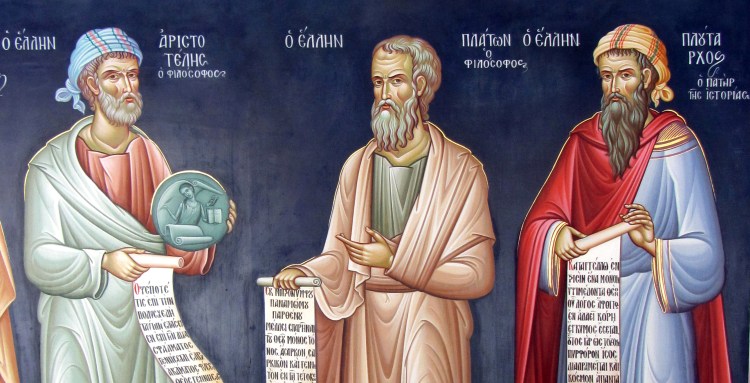

The Ancient Greek philosophers came remarkably close to the truth of man and God even without the benefit of divine revelation. In the 4th century, their teaching became key for developing our present understanding of who Jesus is, of who man is, and our theology of the Holy Trinity. Because of this you can often find their icons on the walls of monastery chapels.

The Gospels and Epistles of the New Testament are the primary sources of authority and dogma in the Church. They, along with the Apostolic teaching, provide the outlines of our theology—our understanding of God, our anthropology—our understanding of man, and our soteriology—how man relates to God and the eternal implications of that relationship. Books like the Gospel of James from the lowest tier of the scriptural hierarchy color in the outline and add light and shading. They provide a more complete view, and to disregard them is only to limit our depth of understanding.

In this Sunday’s Gospel reading, Jesus worries his followers by telling them it is easier to thread a camel through a needle than to get a rich man into heaven. It was alarming because if the rich—who by indication of their wealth were obviously blessed by God—could not get into heaven, what hope do ordinary slobs like me have? “Who then can be saved?”

“What is impossible with men is possible with God.”

Jesus’ answer reminds everyone who hears it, that no matter what we think of our efforts, no matter how pious we are, regardless of the effectiveness of our prayers, we cannot thread the needle into heaven without God.

It is easy to dismiss the stories of James’ Gospel. After all, what are the chances that Mary actually lived in the temple and was fed by an angel? It’s rather difficult, especially with my post-modern educated mind, to believe that the old widower Joseph was chosen to betroth the 12-year-old virgin by a dove emerging from his rod and landing on his head. But “what is impossible with men is possible with God.”

Not only do we attempt to limit the limitless when we discount such stories out of hand as incompatible with natural science, but we miss the point of telling such fantastic stories. It’s the same problem with those who would turn the Genesis creation stories into scientific texts: the story isn’t about how, it’s about why and what that why means to man. They are stories of meaning.

Mary living in the Holy of Holies and fed by an angel, however improbable, tells us the meaning and purpose of her role in our salvation. Whereas, in the first covenant the Holy of Holies housed the container of the Tablets of the Law, words inscribed by the hand of God. Mary will become the new covenant’s Holy of Holies, but this time containing the eternal Word of God Himself, the Second Person of the Holy Trinity. She herself would be the vessel of the New Covenant.

Ultimately, we celebrate this Feast of the Presentation of the Theotokos in the Temple because of who God is. Through the Virgin Mary, God became incarnate. It was she alone who God chose to be a vessel to contain the Uncontainable. That makes her pretty special, and so we commemorate her arrival at the Temple, her preparation for becoming that vessel, preserved in holiness, to be ready to accept the call of the Archangel when he appeared to tell her that she was “blessed among women.”

It is an example that we emulate when we enter the Church for Divine Liturgy: We enter in with a procession of worshipers and saints, we are fed from the Holy Table, and we thence become ourselves containers of the Uncontainable. This is only possible because of the Incarnation and Christ’s work of salvation made it possible, and it is why the central act of Christian worship is called “eucharist,” thanksgiving. Because it is the only genuine response to Jesus’ gift of mercy which made it possible for us to thread the needle into heaven, not just at the end of the age, but now. Because all things are possible with God.