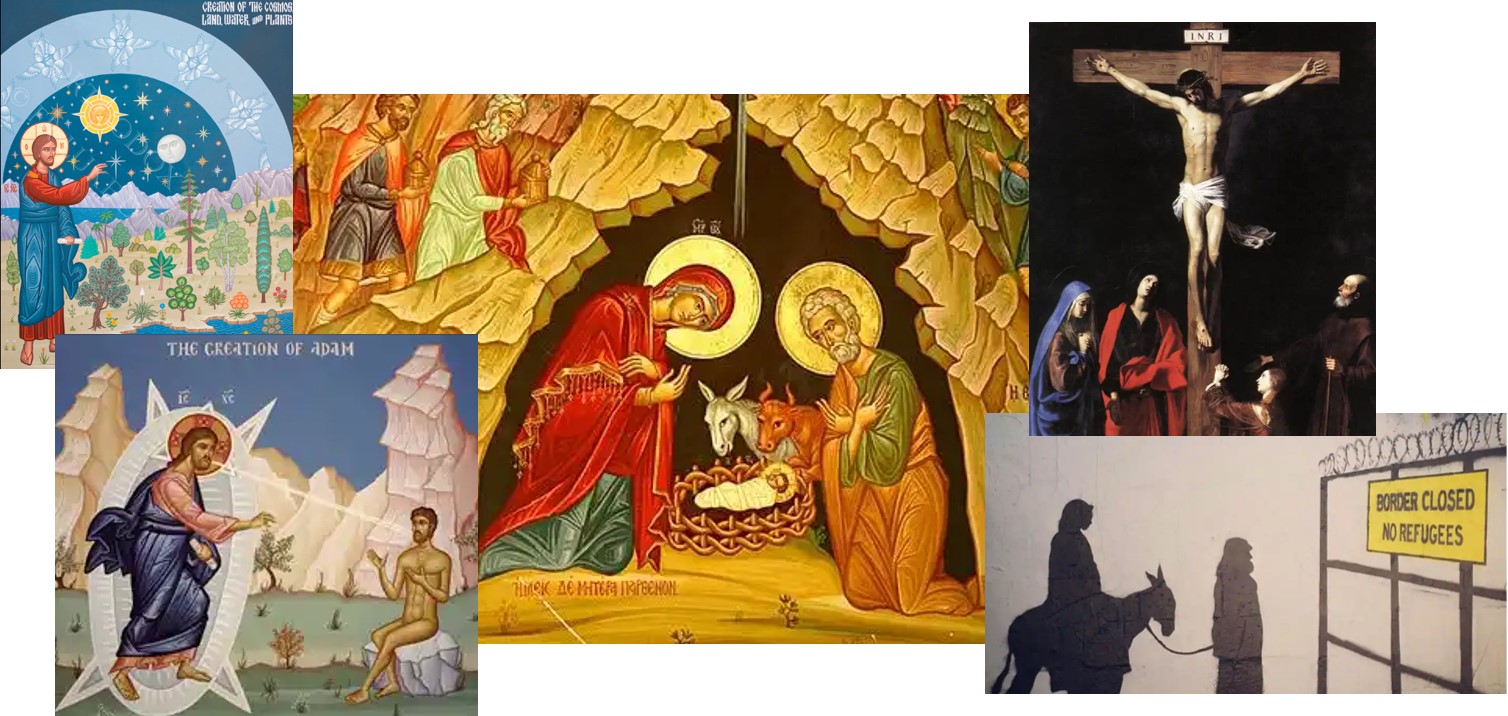

Contrary to a popular holiday meme, Mary and Joseph were not indigent, and they were not refugees. They had no expectations of anyone else providing for their needs and went to the inn knowing payment would be expected. Joseph was a tradesman—a carpenter—and they were in Bethlehem to register themselves in a census so that they could pay their taxes. But nowadays there seems a need to write into the nativity story our own sort of scandal to raise a response from Christians—or anyone—because the story has been told and retold so often that it’s lost the impact of its initial telling. We’re so familiar with the story that it has become comfortable, mundane, and ordinary rather than the scandal it once was. And it was a big scandal.

God was—and is—wholly other, outside of Creation. Before the birth of Christ, God’s participation in His own Creation was only conceivable as a preserver and sustainer. I like to think of a model railroader who builds an elaborate model train layout, so precise in its recreation that you’d think you were looking at an aerial photograph. No matter what he does, no matter how much he’d like to, the modeler cannot climb aboard his trains and drive them. He can only do so from outside of his creation. And this is much like how 1st century Judeans knew and experienced God. The first two commandments make this point very clear.

But then, along comes this man named Jesus, the son of a carpenter from a jerkwater town in the outskirts of Judea. Without any formal education, or credentials of any kind, He upends Jewish society, and his followers begin to gather a stronger and stronger following by preaching the message of Jesus’ life and teaching. Starting as it did within Judaism, this new sect and its teaching comes into conflict with Judaism itself, as well as other religious movements of the time. The followers of “the Way,” as they are first known, are forced to confront questions that demand answers: Just who is this man Jesus? Where did he learn these powerful truths? How did he live such an exemplary and impactful life? Even before His crucifixion, officers of the Jewish courts wondered at Jesus saying that “No man ever spoke as this man does.”

Who is this guy?

The question would cause tremendous turmoil both in and out of the Church for hundreds of years. Was Jesus a man? Is he God? A God? Something in between? These questions bring us back to the scandal of the Incarnation, because what the Fathers of the Church at Nicea in 325 AD and at Constantinople in 381 AD decided, based on Holy Scripture and the experience of the Church, was that Jesus was not some third thing in between God and man, neither was he just a really good man. What the Great Holy Councils proclaimed was that Jesus of Nazareth was—and is—both God AND man.

Now, we’ve recited the Creed so often that this idea just rolls off our tongues without much thought, but to faithful Jews, who cannot even pronounce the name of God aloud, this is the height of blasphemy. To Gnostics who believe that matter is evil and dirty, and that just to create matter God had to first create demigods to do the actual work, the idea of God becoming man is likewise scandalous. So, Jews-turned-Christians in the early centuries of the Church tried several ways to reconcile this idea within their own understanding.

Seeking to emphasize Jesus’ divinity, some, such as the followers of Marcion of Sinope, said that Jesus must have only appeared to be human. This was the Docetist controversy, from the Greek δοκεῖν/δόκησις – to appear or to seem. But as early as the second century, St. Irenaeus decried such ideas, saying that to deny Jesus’ full humanity—to say that he only appeared to be human—is to deny our salvation. Irenaus wrote that if God’s Word

“Only appeared to be in the flesh, His work was not a true one. But what He appeared to be is exactly what He was: God recapitulated in Himself the ancient formation of man, that He might kill sin, deprive death of its power, and vivify man; and therefore His works are true.”

So Jesus had to actually be human. But could He then also be God?

Seeking to preserve the complete otherness and Holiness of the one God was another group, led by an Alexandrian priest named Arius, who taught that Jesus was not begotten of the Father, but was God’s first created being. Arius would famously proclaim that there was “a time when Christ was not,” he would say that Christ was of like essence (ὁμοιούσιος) with the Father, but not of the same essence (ὁμοούσιος). One iota is the difference between heresy and Orthodoxy. It was against the Arians than St. Athanasius wrote that “God became man, so that man could become God,” emphasizing that the fidelity of the original image of God in us could only be restored by the original, by God Himself. So, Jesus had to be God.

Marcionites and Arians were just two of the many religious factions who could not reconcile the idea of God becoming flesh, the divine putting on humanity, the model railroader taking a ride on his train.

It should still be difficult for us to grasp, if we were to give the idea more appropriate thought and reflection than we typically do. That the all-mighty, all-knowing, all-present God limited Himself out of love for His creation that had voluntarily warped itself out of shape from its initial form in its Creator’s image is an idea unique in the history of mankind.

If your faith is only big enough to see the scandal of a pregnant woman denied a room at the inn, then your faith is too small. The scandal is far larger, far deeper than that. Christianity is the only historical faith that proclaims that God loved us enough to become like us, to be vulnerable in the same ways that we are. The scandal is deeper than a God who couldn’t find a home in insensitive hearts, the scandal is that in spite of being unwelcome, God willingly humbled Himself and took on a form subject to discomfort and pain, subject even to death.

The contradictions of God being held, being fed, growing, and learning are captured beautifully by St John Chrysostom when he preaches that

“[The Son of God] became flesh. He did not become God. He was God. Wherefore he became flesh, so that he whom heaven did not contain, a manger would this day receive. He was placed in a manger, so that he, by whom all things are nourished, may receive an infant’s food from his virgin mother. So, the father of all ages, as an infant at the breast, nestles in the virginal arms, that the magi may more easily see him.”

The hymns of the Feast of the Nativity also express this paradox of God becoming flesh:

Before Your Nativity, O Lord, the heavenly hosts trembled in amazement, as they watched the mystery unfold. For You, who adorned the sky with the stars, became a little baby…You, who hold the whole world in Your hand, lay in a manger, a trough meant for beasts. Such was Your plan for our salvation, and thus was Your compassion made known. O Christ, the great mercy, glory to You!

Not only do they express this paradox, but the hymns go even further and express the salvation that comes by Christ’s entry into His creation, extolling us to

Come, let us rejoice in the Lord, as we tell about this mystery. The middle wall of separation has been broken down; the fiery sword has turned back, the Cherubim permits access to the tree of life; and I partake of the delight of Paradise, from which I was cast out because of disobedience. For the exact Image of the Father, the express Image of his eternity, takes the form of a servant, coming forth from a virgin Mother; and He undergoes no change. He remained what He was, true God; and He took up what he was not, becoming human in His love for mankind. Let us cry out to Him: “You who were born from a Virgin, O God, have mercy on us.”

Fr. Patrick Reardon offers the perfect summary of this idea by pointing out that “[Jesus] is both God rendered visible to man and man rendered acceptable to God. For our salvation…He must be both. Were he only a man, His death on the Cross would be unavailing. Were he only God, His Resurrection from the dead would have no significance. If we are truly redeemed, He must be both.”

For no other reason than that He loved us, God became human, became vulnerable, in the most momentous Divine stroke since the creation itself. He remade all of creation by restoring our humanity, joining Himself to creation—to us—in such a way that all of creation celebrates his arrival. As another hymn points out, “each of the creatures made by you offers you its thanks: the Angels, their hymn; the heavens, the Star; the Shepherds, their wonder; the Magi, their gifts; the earth, the Cave; the desert, the Manger.” What are you and I going to give?

By joining Himself to mankind, God has restored the image of His likeness in each and every one of us. You, me, all of us. How will we respond to this gift? A 17th century Christmas Carol offers an answer:

A virgin unspotted, the prophet foretold,

Should bring forth a Savior, which now we behold,

To be our Redeemer from death, hell and sin,

Which Adam’s transgression entangled us in.

Now let us be merry, put sorrow away:

Our Savior, Christ Jesus, was born on this day.

We respond by being merry, and in being merry we become thankful. The proper response to the amazing, scandalous gift of God’s Incarnation is worship. This is why we celebrate this feast with two Divine Liturgies, and not just one: in order to offer our sacrifice of Thanksgiving, our Eucharistic worship, to our Lord and God and Savior Jesus Christ, who has already given us more than we could ever hope to repay.

So as we prepare for and receive Holy Communion, may we be merry and thankful for a God who loved us enough to become like us in every way so that we might become more like Him each and every day. And thus carry the light of Christ into the world by being merry and thankful in all of our interactions with our fellow men who also bear the image of our Creator, likewise restored by the Incarnation of our Lord, and God, and Savior Jesus Christ, which we celebrate on this bright and beautiful feast.

Merry Christmas, Καλά Χριστούγεννα!